The Prediction Market Industry’s Gambling Problem Has A Name: Gambling

Operators can keep workshopping terminology, but a sports bet is a sports bet is a sports bet

4 min

Last week, 60 Minutes ran a puff piece on Polymarket.

In the first 10 seconds, Polymarket founder and CEO Shayne Coplan answered a question from host Anderson Cooper, namely, “What is Polymarket?”

Coplan’s answer was simple, direct, to the point, and 100% true:

“It’s a site where you can basically bet on current events. Some sort of question about the future event, like an election, and as a result, when a ton of people are betting, you get the betting odds, which basically tell you how likely each outcome is.”

I’m going to reprint the above statement from Coplan, but I’m going to judiciously add some all-caps and bold lettering to a few of the words for emphasis.

“It’s a site where you can basically BET on current events. Some sort of question about the future event, like an election, and as a result, when a ton of people are BETTING, you get the BETTING odds, which basically tell you how likely each outcome is.”

So we’re clear, yes? People BET when they are on prediction markets. If you like, replace “current events” with “sports” and “election” with “an NFL game,” and it becomes pretty flipping clear where Coplan’s head is at. I’ll do it for you.

“It’s a site where you can basically BET on SPORTS. Some sort of question about the future event, like an NFL GAME, and as a result, when a ton of people are BETTING, you get the BETTING odds, which basically tell you how likely each outcome is.”

I’d like to follow Coplan’s admission-by-any-other name with a tweet from a guy who has like 2,000 followers, but the tweet in question was seen more than 4 million times.

He says Kalshi — and, by extension, all prediction markets — isn’t gambling and points to a United States Court of Appeals decision to prove his point.

So we’re clear, he says people are not gambling when they are on prediction markets.

So which is it? Are prediction markets gambling, or are they not?

Well, that appeals decision called the distinction “close and difficult” and was only really ruling on whether election betting would be considered gambling. The court was like, “well, elections aren’t games,” so that’s where they landed.

To be abundantly clear: The court didn’t say prediction markets aren’t gambling; it said election contracts don’t qualify because elections aren’t “games.” That’s a narrow holding. The moment you shift to something that is a game — like, say, gee, I dunno, sports — the logic collapses instantly.

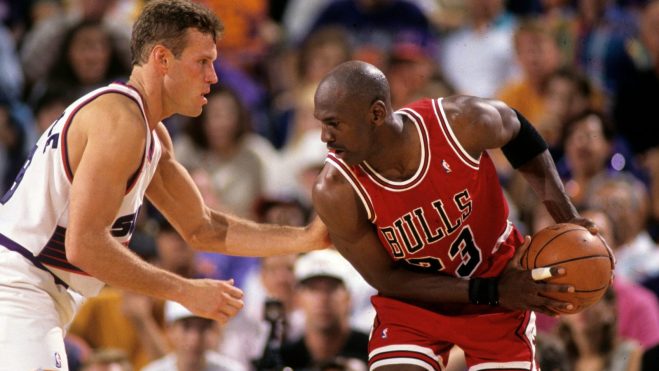

After all, sports are games. We call them games. And when we put money on them, we call them gambling, and …

Oh, for the love of god, of course “buying a contract on an NFL game” is gambling.

And everyone else seems to have come to that agreement this past week.

Industry perspectives

Steve Ruddock, writing in his Straight to the Point substack: “I feel like Elaine watching everyone in the diner eat their candy bars with a knife and fork: ‘What’s wrong with all you people!? Have you all gone mad?’”

Dustin Gouker, writing in his The Closing Line substack: “This is the very dumbest part of the rise of prediction markets, at least in my book: That it feels impossible to have an honest conversation about what’s actually going on at these sites and apps. We can’t separate legal arguments from common sense.”

Gouker was writing in response to a statement by Matt King, Fanatics Betting CEO, who insisted in a Sportico piece that betting on sports via prediction markets is “trading.” (Kudos to the Sportico headline writers, as “Fanatics Launches Prediction Market — Without The G-Word” is chef’s kiss.)

But it’s not just gambling journalists who have had enough. Bloomberg Markets magazine’s latest issue dives right into all of this, dedicating the entire issue to what is gambling and what is investing.

Nigel Eccles, the founder of FanDuel and now crypto casino BetHog, had a pair of tweets last week that plunged into the controversy.

The first one was cheeky, noting the line between gambling and predicting was actually lineless.

The second tweet was less cheeky and even more on point.

We’ve gotten to the point where Eccles — who, again, founded FanDuel — has to be the person in the room to say we need to ID gambling when it’s clearly gambling.

Never mind, of course, his position 10 years ago, when the New York attorney general kicked off the anti-DFS crusade by banning FanDuel in the Empire State, saying it was gambling, to which Eccles said, “We’re a legal game.”

Of course, daily fantasy sports managed to eventually thread the needle, becoming legal in 27 states and D.C., unregulated in 19, and illegal in five.

I love DFS. I play DFS every day. It’s definitely a game of skill, but come on: It’s also gambling.

DFS survived because lawmakers carved out a “skill game” lane for it. Prediction market sports betting has no such carve-out and no plausible one coming.

And while I can sit here and listen to an argument about elections or the course of war in Ukraine or how long MrBeast’s next interview will be as valid prediction markets that can be seen as “investing” as opposed to all-out “gambling,” sports betting by any other name is still sports betting.

Cards on the table

Look, I get it. I understand the game being played here.

Prediction markets don’t want to call their products gambling because the second they do, they’re subject to all the regulations, all the licensing requirements, all the taxation that comes with being a gambling company. They want to be seen as information markets, as financial instruments, as anything-but-gambling.

And honestly? That might work for a minute. Maybe even a year or two.

But the semantics are going to catch up.

Because when you’re taking bets on whether Patrick Mahomes throws for over 250 yards, you’re not running an information market. You’re running a sportsbook. When you’re offering odds on NFL games and taking a cut of every transaction, you’re a bookie with a better thesaurus.

The more I think about it, the more this is the “I did not have sexual relations with that woman” of our times, you know?

The prediction market industry players can keep insisting they’re doing something fundamentally different. They can keep workshopping their terminology and coaching their executives on which words to avoid in interviews. They can point to court decisions and legal frameworks and claim they’ve found some magical loophole.

But at some point, and probably sooner than they think, regulators, legislators, and the general public are going to look at a screen showing Chiefs -3.5 and Eagles +7 and say, “Um, yeah, that’s gambling.” (And that’s without even entertaining the possibility of prediction markets including online casino games.)

When these things happen, all the semantic gymnastics in the world won’t matter.

Call it what it is. Because pretending otherwise just makes the inevitable reckoning that much worse.

Or not. I’m waiting to see where that question opens on Polymarket and Kalshi.